KAYA NOTEBOOM is a writer from Portland, Oregon. She writes a monthly arts column for Variable West and has published essays and reviews with Public Parking Magazine and Variable West. She also keeps a neglected Substack. Kaya is getting a masters in Critical Studies at PNCA where she is reading about suicidality, spirituality, logics of self-annihilation, and aesthetics of ambivalence towards life.

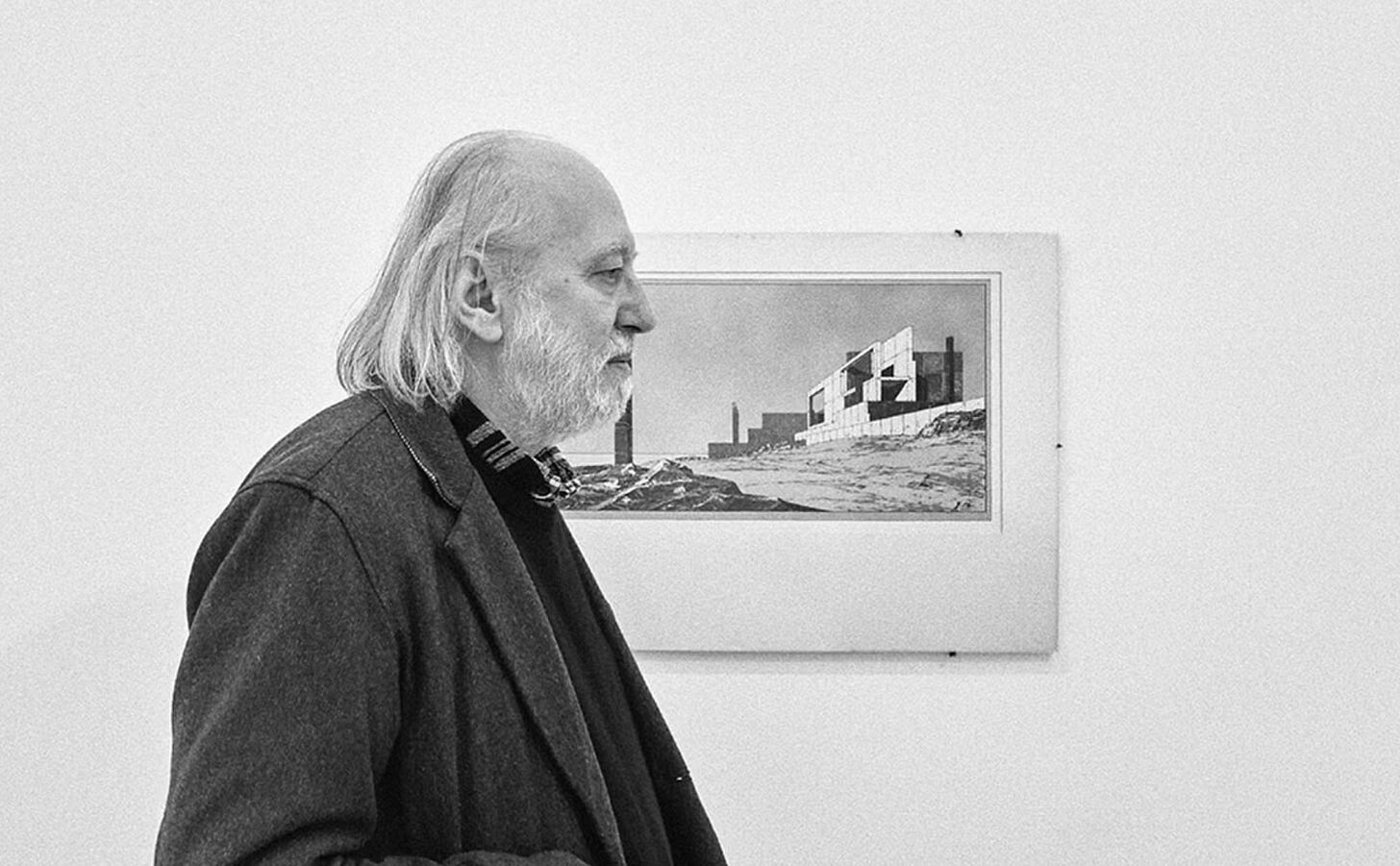

LÁSZLÓ KRASZNAHORKAI is a Hungarian novelist and screenwriter known for difficult and demanding novels, often labeled postmodern, with dystopian and melancholic themes. Several of his works, including his novels Satantango (Sátántangó, 1985) and The Melancholy of Resistance (Az ellenállás melankóliája, 1989), have been turned into feature films by Hungarian film director Béla Tarr.

Kaya Noteboom, 12:32 PM

Hi Edy!

You, 12:33 PM

Hello Kaya! Dear friend, writer. I'm grateful and excited that you've agreed to do this with me... what I'm loosely calling Intertext Messenger atm.

Kaya Noteboom, 12:33 PM

I think that’s a great name for it. Glad and honored to be here and doing this.

This form is already making me want to say some unhinged stuff. Excited to see how this will go!

You, 12:34 PM

I love to hear it. Which is so perfect, also, because we're here to discuss László Krasnahorkai.

Kaya Noteboom, 12:36 PM

The big LK. He’s huge into annihilation and infinity, and I was reminded of both when I logged into g-chat for the first time since sophomore year of high school.

You, 12:37 PM

I had no idea it still existed and something about this being our mode of communication feels just right.

Can you say more about the infinitude in his work and how you're reading it?

Kaya Noteboom, 12:43 PM

I was reading the first story in The World Goes On last night, and it’s basically this guy who is in a miserable and bleak and cold place, and he knows he has to move but he feels paralyzed by his options—he could go anywhere. Then he goes everywhere, never stopping like the hands of a clock except he “doesn’t mean anything” like a clock-hand does. People hate this guy who doesn’t stop moving. And then basically you find out in the last few lines that he was actually still standing in the same spot the whole time. And it’s like this cosmic joke that’s played on this guy but also on the reader.

Kaya Noteboom, 12:43 PM

And it’s written in third-person. This third-person narrator moves through bleak characters, time, geographies like it’s air.

LK has this elastic vision that can stretch subjectivities like silly putty. And it’s tempting to do that in a way that feigns importance in an annoying way, but this guy is hilarious. Comedy, humor, that’s the language of eternity to me.

You, 12:47 PM

It sounds hilarious, but also pointed like someone specifically is getting a joke played on them and if you're not down for a little introspection or self-checking it's you, you're the one getting played, which might make you feel inadequate or uncomfortable.

The fact that this character is a bit like a metaphorical clock makes me think LK is messing with us in a strategic way...

Kaya Noteboom, 12:49 PM

Totally. I mean that was my first reaction to his style. I was pissed. After 10 pages I put it down for four years. This was Seibo There Below. But then when I finally surrendered to it, that book made me believe in art and god again.

You, 12:51 PM

I think putting his books down for years at a time is a constant. I read an interview on NYT where someone said the same thing. It's like he wants to deter his readers, or like he only wants the readers that are willing to go to war to read him.

Kaya Noteboom, 12:52 PM

It feels taunting in a way that’s also playful. I grew up being teased by my family a lot and that’s always been an energy that I’m drawn to. But I think it’s powerful proof of the relationship that readers and writers can have that’s not just metaphorical.

The auto-fictional impulse today encourages a sort of parasocial relationship with readers in a way that feels so one-sided to me. It feels so obvious that LK is reaching out, not just letting us peer through as voyeurs. He engages something more active, but somehow also not agential.

You, 12:56 PM

What you're describing is mysterious. A sensation that I think people who read as children as a kind of survival or method of avoidance really understand. Godly. And I do want to talk about god more because lately I've been feeling this urgency to reinstall some object-oriented (god, Jesus, some fixed image) belief back into my life, but most options feel super off.

How did LK convince you of god again?

Kaya Noteboom, 1:01 PM

I like what you said about going to war to read him. He’s from Hungary but has been living in exile for decades I think. I don’t know a lot about the situation in Hungary but I think there’s something about fleeing in his writing, fleeing the place you are or even the person you are. His prose is a paranoid sprawl, almost desperate. The elasticity and tempering with distance in his writing is at times transcendental, like how god sees. But he uses this god-trick to get down in the gutter, with characters and thoughts that importantly have no social importance. This immanent conscience in the novel is so earthy, so muddy. I think his god thinks disposable, boring, or crazy people are the most important. I like this god.

Kaya Noteboom, 58 min

I wanna hear more about this urgent draw towards something god-like!

You, 54 min

In an interview I watched he said he was quite literally fleeing from war. He was enlisted once after his first year of university and he almost died. It was mandatory that if you didn’t finish university you had to enlist again. He refused! And left his upper middle-class family to live with the poor in various counties in Hungary. These areas were communist for the most part (he noted how the people there were oppressed in very similar ways as with other systems). Every 3-6 months he would move to avoid the military bureau finding him.

Kaya Noteboom, 54 min

Ok that is so helpful!

You, 53 min

I do believe externalizing positive affects like faith, hope, etc. are important and during periods of my life they've been vital. You wrote this about LK's book War & War:

“I began to relish disappearing into another person’s faith and I began to long for one of my own. Where is my manuscript? Where is my conviction?”

Kaya Noteboom, 52 min

Oh yes. Conviction. My white whale.

You, 51 min

My draw toward god is something like that... "disappearing into another person's faith.” It's part escapism, part self-annihilation, part relief and freedom. This mix of aspirations that if believed amount to, maybe, a realization of god?

What does conviction do for you?

Kaya Noteboom, 49 min

Disappearing into someone else’s faith is totally escapism. But now I really believe, and I think this is one motivation for asking for my own conviction, is that another person’s faith can only take me so far, and it may lead me in an artificial direction. I think the kind of self-annihilation that can be freeing or relieving comes from finding a faith of my own. Faith and conviction are different, but conviction for me is something I could hold onto even with a gun to my head or my arm torn off.

You, 42 min

Does writing support this sense of conviction?

Kaya Noteboom, 37 min

Writing is definitely how I’ve gone about trying to find or cultivate conviction. However, I think writing isn’t enough. I wonder if locating conviction comes from more passive activities that are actually very active. Like paying attention. Like sitting still for a very long time. Writing, I think, can feel like conviction, but I think maybe it’s too busy and declarative of a thing for me to be able to sense conviction long enough to hold onto it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Intertext to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.